In late spring, nature cheerily announces that summer is on its way by bestowing the fields of rapeseed with an explosion of yellow. The vibrant colour is typical of rapeseed’s wider family — mustard (or Brassicaeae), but you are also looking at an important source of oil for both cooking and biofuels.

1) The main image above shows the molecular structure of glyceryl trioleate on a photograph of fields near Nailsea in North Somerset – you can see yellow fields of rapeseed in the background. This photo was taken in 2017, well before the COVID-19 lockdown, so we were allowed out of the labs. Note that while we tend to draw molecular structures long and flat, the attractions between chains (van der Waals) actually make them curl up around each other. This is something you can observe in other images as well, for example for chillis and sunflowers.

If you are a hay fever sufferer, or just a particularly observant individual, then you may have noticed that there is an ever expanding population of rapeseed fields. World rapeseed production has seen a dramatic increase (5 to 70 million tonnes to be precise – United States Department of Agriculture, November 2016) over the past 50 years due to its increased use as an alternative cooking oil and also in the production of biofuels.

Records suggest that rapeseed (Brassica napus) has been cultivated in Europe since the 13th century for use as food and smokeless fuel oil — for lamps, not cars! Consumption of other members of the Brassica genus – the turnip (Brassica rapa subsp. rapa) and broccoli (Brassica oleracea) – can actually be dated back to Roman times.

Canada is currently the world’s leading rapeseed-growing nation, having produced an estimated 18 million metric tonnes each year, but it wasn’t always this way. Towards the end of the 1930s, Europe and Asia were providing North America with rapeseed oil, as it was an effective lubricant of steam engines. When the Second World War broke out, the rapeseed supply was cut off, so North America needed to start mass-producing its own rapeseed for the steam-powered marine vessels. Canada and the U.S. invested a lot of money and resources to develop the industry. Rapeseed demand saw a rapid decline after the war ended when huge quantities of marine engine lubricants were no longer required and engines started to progress towards diesel power, instead of steam.

Close-up image of a rapeseed plant.

However, all was not lost! During the war years Canada also concluded that its domestic edible oil production was insufficient, and rapeseed had proven itself as a hardy crop that could flourish in the prairie climates, unlike sunflowers and soybeans. Unfortunately the rapeseed oil that the Canadians were producing for lubricant was toxic to humans and unsuitable for livestock feed, but this didn’t deter them. Chemists collaborated with seed breeders on their research and eventually (in 1973) Keith Downey and Baldur Stefansson developed double zero varieties of oilseed rape (“rapeseed 00”). Double zero or double low denotes that the oil contains low concentrations of anti-nutritive erucic acid (specifically <2%) and glucosinolates (<30 µmol). To avoid confusion between the new healthy oil and the old lube they renamed the double zero plants “canola” – derived from Canada oil.

2) Glucosinolates are a family of nitrogen and sulphur containing compounds that are derived from glucose and amino acids (figure 1). Glucose is the sugar made by plants in photosynthesis and it is what flows around us humans as blood sugar. Glucose is also formed in the thermal decomposition of sucrose – the sugar in sweets (see our blogpost about sugar). The variation of the side group, R, in the glucosinolates (Fig. 1) is responsible for the variation in the biological activity of the compounds.

The breakdown of glucosinolates when ingested is responsible for the pungent taste of mustard and horseradish sauces, and also for the bitter taste of Brussels sprouts. The decomposition of glucosinolates occurs in the presence of myrosinase, an enzyme which is present in rapeseed but which is physically separated from the glucosinolates until the seed is crushed – this has been termed a ‘mustard-oil bomb’, and is a defence mechanism that brassicas employ to stop being eaten by insects (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2002, 99, 11223-11228). In rapeseed this process forms a particular isothiocyanate (N=C=S functional group) which readily cyclises to give a compound named goitrin (Nutr. Rev., 2016, 74, 248–258). Goitrin interferes with hormonal processes in your thyroid, resulting in enlarged thyroid glands (goitre). Surprisingly, isothiocyanate compounds like these also possess anti-tumourogenic qualities and have shown strong potency against melanoma and drug-resistant leukaemia (Acta Pharmacol. Sin., 2009, 30, 501–512).

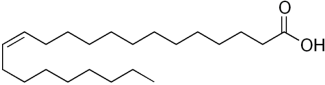

Erucic acid (Figure 2) is a monounsaturated omega-9 fatty acid which is thought to be toxic to humans and animals. It contains only one C=C double bond (monounsaturated) and this is on the 9th carbon from the alkyl tail (omega-9). Studies have shown a correlation between high erucic acid content of rapeseed and heart lesions in rats that were fed with it (Can. J. Comp. Med., 1975, 39, 261–269).

Thankfully the development of “rapeseed 00” by the Canadians removed these two compounds so now we can enjoy the extensive health benefits of consuming the oil without having to worry about the nasties. Rapeseed has the lowest saturated fat content of any culinary oil and half the saturated fat content of the pricier olive oil. Rapeseed oil also has high levels of mono- and polyunsaturated fats that are linked to lowering the risk of coronary heart disease. Oleic acid is a monounsaturated fatty acid that is the main constituent of rapeseed oil (61%) and it exists in the triglyceride form (glyceryl triolate – as shown in the main image above).

A mixture of 4 parts glyceryl triolate and 1 part glyceryl trierucate (the triglyceride form of erucic acid) is known as Lorenzo’s oil. Susan Sarandon starred in the 1992 film of the same name which tells the true story of Augusto and Michaela Odone, two non-scientists who formulated the medicine for their son Lorenzo, who was diagnosed with adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) when he was five years old (Lancet, 2009, 373, 888-889).

3) As well as providing us with high-protein animal feed, medicine and a healthy cooking oil, rapeseed oil can also be used as a biodiesel. Contrary to popular belief biofuels aren’t a new concept. Rudolf Diesel, the inventor of the diesel engine, ran successful tests on vegetable oils as fuels for his engine 100 years ago, and Henry Ford originally designed his Model T to run on ethanol. Biodiesel can be used in the pure form of fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) or mixed with diesel (30% biofuel).

A field of rapeseed.

Transesterification of rapeseed oil with methanol is the cheapest and least problematic method of obtaining biodiesel (figure 3). The reaction is reversible due to the formation of water, so, to shift the position of equilibrium towards the products, an excess of methanol should be used. A basic catalyst (KOH) is employed so that the reaction can proceed at room temperature, and anhydrous reactants must be used as water decomposes the catalyst and also shifts the equilibrium towards reactants. Combining refined oil and anhydrous methanol with high purity results in a high content of desirable methyl esters in the biodiesel (96-99%) (Plant Breed. Biotech., 2016, 4, 123-134).

The reaction produces glycerol as well as biodiesel. The cost of obtaining crude glycerol during esterification of vegetable oils is less than the traditional method involving splitting of fats; the glycerol produced can be used to make soap or explosives (the fat stealing scene in Fight Club could have been avoided!)

So it’s not just a pretty flower after all.

Contributors: Tom Faulkner, Tim Harrison, Angus Voice, Lucy Bird, Chris Adams, Simon Perks and Natalie Fey